Music triage: flood relief in North Carolina, health care in New York.

An excellent 136-song compilation of previously unreleased music (R.E.M., Jeff Tweedy, etc.) raises money for the Asheville region. A Hudson Valley festival connects musicians w/ free health care.

It’s been a rough week for a lot of folks everywhere, particularly here in the U.S. So I scrapped the newsletter I’d planned for this week to stump for a couple of benefit projects.

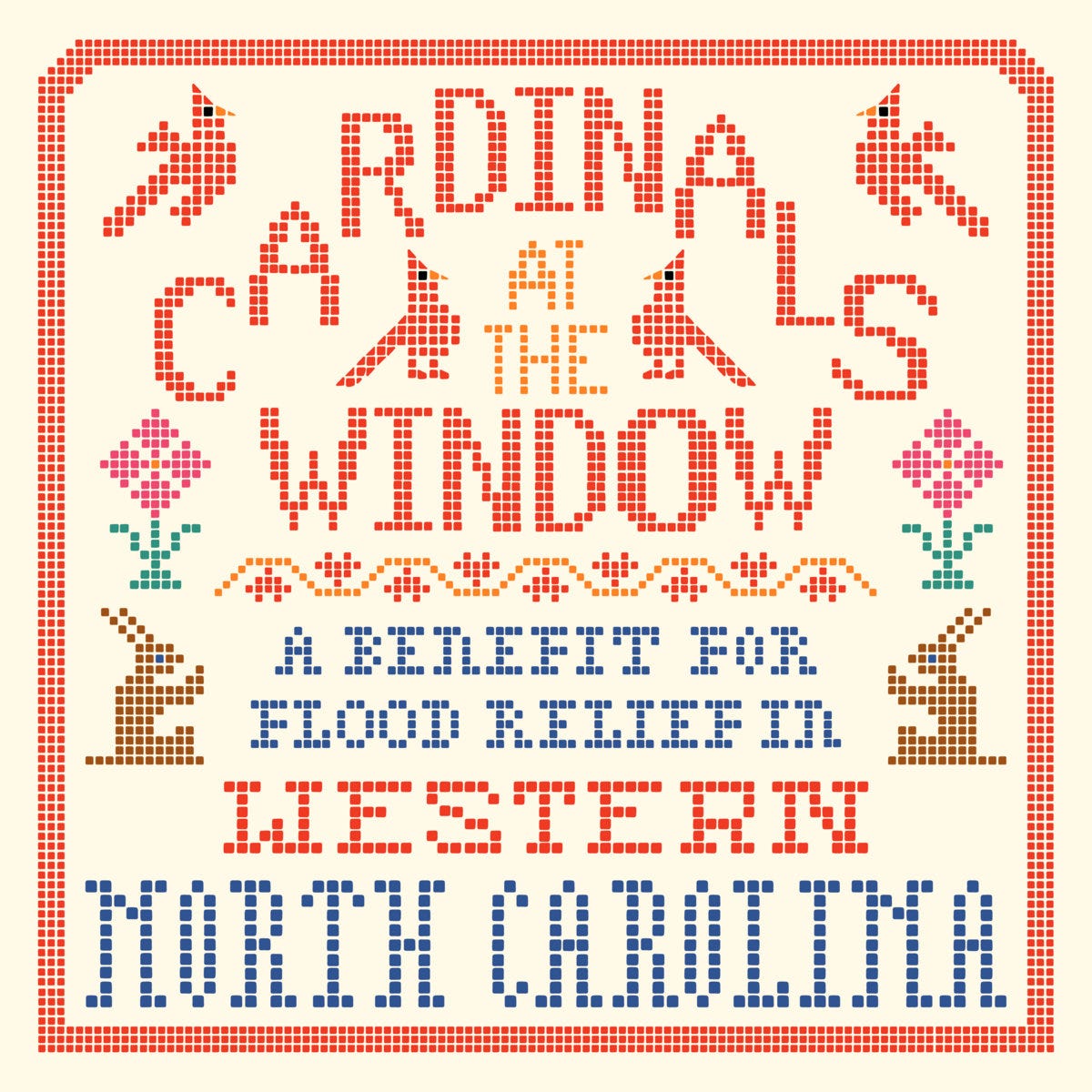

The arts community in North Carolina was especially hard-hit by recent storms — Asheville in particular, an important city in the American indie music eco-system. With remarkable speed, that community mobilized to assemble a tremendous 136-track digital compilation, available on Bandcamp for a mere $10. It’s top shelf stuff, much of it previously unreleased — a collection I’d cover even if there wasn’t an emergency to address.

It’s got brand new, non-LP tracks from artists whose new albums will definitely be on my Best of 2024 list, including MJ Lenderman (the gorgeous “Pianos”) and Rosali (the soaring “Hey Heron”). There are new songs from Sharon Van Etten, the Mountain Goats, Sylvan Esso, and Wednesday’s Karly Hartzman (who told me a couple months ago that she’s settling in after the band’s summer tour to work on a solo album). There are previously-unreleased live tracks from Jeff Tweedy (w/ Hartzman), R.E.M., War on Drugs, Tyler Childers, Fleet Foxes (“Blue Ridge Mountains,” of course), Drive-By Truckers, Superchunk, Gillian Welch & David Rawlings (their beautiful new “Hashtag”).

There are also some great covers. Waxahatchee does Welch’s “Wrecking Ball.” Iron & Wine do the Bee Gees’ “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart.” Adeem the Artist does a lovely version of Elizabeth Cotten’s “Freight Train.”

Many of the artists are from the region. I guarantee you will discover some new favorites. I discovered Sluice, aka Winston-Salem musician Justin Edward Morris, whose exacting cover of Gillian Welch’s “Hard Times” pretty well gutted me.

100% of the proceeds are being split evenly between Community Foundation of Western North Carolina, Rural Organizing and Resilience (ROAR), and BeLoved Asheville.

Here’s the link again. Just $10, and worth every cent.

Below you can read the moving liner notes, by Asheville music scene mainstay Rusty Sutton and esteemed music journalist Grayson Haver Currin.

I was raised and still live in a community five miles west of Asheville, North Carolina, called Candler. Over the last 40 years, I’ve watched it transition from a small rural outpost into suburbs. The face of our community has taken a variety of new shapes along the way. From 160,000 the year I was born, the population of our county has ballooned to 275,000.

One thing has remained constant: We’re river people. We identify as Mountain Folk, but the truth of it is, we’re river people. The rivers and springs of our home have been the lifeblood of our communities for generations. The mountains are hard, unforgiving land, so it’s the natural waterways that make it habitable. The mighty French Broad that runs through the center of town—along with the Swannanoa, Green, Hominy, Pigeon, Oconaluftee, and others—sustains us. Near the turn of the last century, one of my great, great uncles earned the honor of becoming North Carolina’s oldest living man. He claimed that it was a result of daily plunges into the icy waters of Cataloochee Creek.

On September 27, 2024, I watched as the rivers began to take back what they had given us for so many generations. To say that we were unprepared would be a mistake. We’ve learned the hard way about floods: where they happen, how they impact us, what works, what doesn’t. In 2004, I was in college in Chapel Hill when friends who attended Western Carolina University drove several hours to sleep on my couch and floor as we watched news of what we were told then was a “once-in-a-lifetime storm.” It eradicated the downtowns of Biltmore Village, Clyde, Canton, and others. They returned and started putting the pieces back together.

This time was different. Not only was our collective hubris about how often we’d been seized by flooding on full display, but the scale was unlike anything we’d ever experienced. Communities were drowned. We lost power and then cell service and then water. The radio reported that the only interstates and highways that could carry supplies and lives in or out were impassable from landslides and collapsed bridges. Food, gas, and water became accessible only to those with cash, solar panels, or hand-pumped wells. The haves and have-nots were starkly divided, but, to be totally honest, no one truly had all they needed. Thousands went straight into survival mode and, for the most part, handled the situation collectively. Resource management became a complex formula that most of us have never had to navigate; the stakes of that calculus became, well, mountainous.

My family, which includes three generations of people who have mostly lived their entire lives in Candler, got out as soon as we were able. It was hard to decide whether to stay and help or leave. For us, it became a question of whether we’d actually be of service or just another gaggle of people in line at water distribution centers or gas stations. We had the means to leave and felt it only right to go, to avoid taxing the dwindling resource supply.

Now we’re working to help get more food, water, gas, diapers, formula and cash back into the area. It won’t happen overnight, and there won’t be one fix that comes from a single government agency or aid organization. It must be a network of efforts happening, both at once and over a long period of time, to put it all back together.

After driving out of the Blue Ridge, I finally reached a place with a reliable cell signal. It was an overwhelming and bittersweet experience. We were flooded with images of what our friends and neighbors were going through in further-flung parts of Western North Carolina. We also received a massive amount of concern and love from friends and loved ones around the world, including the people organizing this benefit. The funds raised by this effort will end up in the coffers of people on the ground doing good, impactful work in the region.

Give what you can. Hug your friends and family. Use our experience to illuminate what, unfortunately, this new future will be like for us all: always on the precipice of climate disaster. It’s a stark, cold reality, and we’ll only get through it together. A friend of mine who stayed behind to spearhead aid efforts in his neighborhood shared these words earlier, and I think they’ll live with me forever: “Our terrain wasn’t meant to handle this storm, but our community was built for the aftermath.”

—Rusty Sutton

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

My fondest memories of Western North Carolina all involve the rain. There was my first wedding anniversary, sitting on a cabin high above Hot Springs, watching the weather roll in over a ridge as if it were god’s very breath. There was the time years later when we visited the home we’d eventually buy, also outside of Hot Springs, and got our van intractably stuck in mud. We sat on the porch, watching the water come down and deciding this was home just as we heard a tow truck rumble up the long dirt road. And then there was the time, again years later, we took a day off in that very home while walking 2,200 miles northward on the Appalachian Trail, eating ice cream by the pint as it poured outside.

More than any other mountain range in the United States, water helps make the Appalachians special, so green in the summer that it can feel like no other color exists. The peaks are old and worn, so that the spaces between mountaintop and the gaps or valleys, where the creeks and rivers run, is rarely very large. I have traveled most of this country’s mountain ranges by foot now, and I remain spellbound by the way earth and water exist in perfect tandem in the Appalachians. They have coexisted for so many millions of years that they seem a perfect system, a distillation of deep time before our very eyes.

Sometimes, of course, even seemingly perfect systems temporarily fail, overrunning our own human designs and desires. In recent weeks, the world watched with increasing horror as the suddenly unnatural waters of Appalachia overran entire communities and cities, towns and farms. Places so many of us have loved for so long may now only exist as fading memories and lingering highwater marks, devastated not only by nature but also the fundamental ways we have changed nature. For some of us, it is a tragedy beyond imagination; for others on the ground, it is absolute reality.

Cardinals at the Window—named for an expression we’ve all heard in Appalachia, meaning that there’s a little luck on the way—is our modest attempt to help the best we can, to do what we might to help restore some small piece of a place so many of us love so much. Friends far and wide instantly offered up their work, only with the caveat that there be something more they could soon do, too. It is very tempting to curse the rain and the water that drowned and destroyed so much of Appalachia. Most of the time, though, it is part of what makes the place special, unforgettable, unique—a home worth keeping, where land and water and sky merge into perfect union, natural and spellbinding.

—Grayson Haver Currin

Missing Home, Colorado

Closer to home for me, the Annual O+ Music and Arts festival starts today (Friday Oct 11) headlined by fellow Substacker Neko Case and Kate Pierson, the magnificent voice of the B-52’s. It’s geared towards connecting artists and musicians with free and affordable health care, which is tragically hard to come by in the United States, as many of y’all know. Here’s a link to learn more about what the O+ group does. And here’s the link for festival tickets. If you’re in the Mid-Hudson region this weekend, check it out — it’s a suggested donation/pay-what-you-can scheme (ie: free, if necessary) and it’s always a beautiful celebration of community, creativity, and people caring for one another.

Catch ya soon, Will